Not Just Waste-pickers: The Rise of Baramati’s Safai Saathis

In the heart of Baramati, under the scorching sun, a quiet revolution is taking place. It’s not on a factory floor or in a boardroom. It’s in the hands of women and men who were once part of the invisible workforce — safai saathis (waste-pickers) working individually, unseen and underpaid, recovering only what was deemed "valuable" by the market.

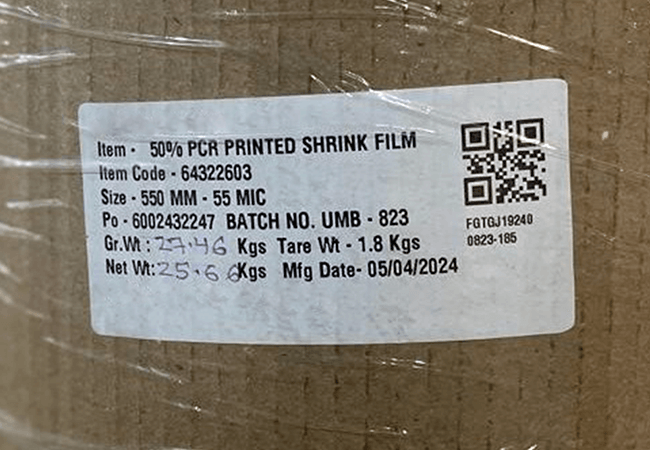

Historically, safai saathis have gravitated toward rigid plastics — solid bottles, containers, and hard packaging that could fetch them a few rupees. These were the materials the market recognised. Flexibles — multi-layered plastic wrappers, film, bags — were seen as worthless, destined for incinerators or to sit in open landfills, slowly disintegrating into the earth, adding to the ever-growing mountain of legacy waste.

But all of that is beginning to change.

About 2 years ago, the men and women who now operate in the Baramati collection centre were working under the harsh open sky, sifting through garbage, earning barely enough to feed their families. They would collect whatever rigids they could find, walk long distances to, hoping a larger kabadiwala would buy them — always at a price the kabadiwala dictated.

Flexibles? They didn’t even bother.

There was no buyer, no price, no value. Just more & more plastic mounting in landfills.

This is why we stepped in – to solve 2 core problems with 1 solution. Today, these same safai saathi’s work in a shaded, well-ventilated centre. They work for themselves, work as a group and come to work because they want to. They now all of Baramati’s household waste - both rigids and flexibles. And when we buy the material directly from them , the control is finally in their hands. No middlemen, no arbitrary pricing — just steady work, fair pay, and a growing sense of dignity.

Another invisible impact of this initiative has been on children — and their futures.

In the older, informal system, it wasn’t uncommon for children to accompany their parents to sort through waste. Today, with the centre operating under formal guidelines, only the people working in the centre (all adult)s are allowed inside. The environment is safer, more structured, and children are no longer part of the labour. It’s a small but critical shift — one that helps keep children where they belong: in schools, at play, and away from waste piles.

The most powerful shift, perhaps, has been psychological. The flexible packaging that once had no worth is now collected, weighed, and bought by us for recycling. It is being returned directly into the circular economy — no longer a pollutant, but a resource.

For the safai saathis handling it, this shift signals something bigger than economics. It’s about acknowledgment. It's about telling them that what they do matters — that they matter.

One of the safai saathis shared, “Pehle toh lagta tha hume kuch bhi mil jaaye, bech ke kal ka guzara ho jayega. Ab lagta hai ki jo hum kar rahe hai vo asli kaam hai, hum kuch badal rahe hain.”

(Earlier, it felt like what ever we get at least we will be able to sell it to get through the next day –Now it feels like we’re doing real work, we’re changing something.)

The success in Baramati is a glimpse into a more inclusive future — one where we don’t just clean up our cities, but uplift the people who do it for us. Where systems are designed not just for efficiency, but for equity. Where plastics, even the forgotten ones, are not discarded.